The Aquatic Cyborg

What 160,000-year-old whale barnacles tell us about the origins of complex society

December 20, 2025

The standard textbook story of human social evolution goes something like this: for most of our 300,000-year history, Homo sapiens lived in small, mobile, egalitarian bands. We roamed the savanna, hunting game and gathering plants. Complexity---hierarchy, sedentism, division of labor---only emerged after the Neolithic Revolution, when agriculture forced us into villages and gave rise to surplus, property, and power.

It's a clean narrative. It's also probably wrong.

A 2022 paper by Singh and Glowacki in Evolution and Human Behavior makes a strong case against this "nomadic-egalitarian model" using comparative ethnography and a growing archaeological record. Their conclusion: social complexity didn't require agriculture. It required predictable resources. And the most predictable resources in the Late Pleistocene weren't on land---they were in the water.

The Evidence: Barnacles, Middens, and Deep-Sea Fish

At Pinnacle Point Cave 13B in South Africa (~164,000 years ago), people weren't just dabbling at the shoreline: marine foods show up systematically, and even a fragment of a whale barnacle---an organism that lives attached to whales---suggests that whale tissue entered the human food chain. The conservative reading is scavenging a stranded whale, but even that implies planning, transport, and social coordination around a rare, massive resource pulse. (You don't make use of a whale carcass at scale without a plan and a rope.)

Pinnacle Point is unusually early; later, similar patterns become widespread. By 130,000 years ago, shell middens (accumulated piles of shellfish remains) appear across multiple African coastlines. These aren't the traces of opportunistic beachcombers. They're the signatures of sedentary populations systematically exploiting marine resources.

The pattern repeats globally. Wherever we find "dense, rich, and predictable" aquatic resources---salmon runs in the Pacific Northwest, maritime environments in Tierra del Fuego, coastal shell beds---we find low-mobility foragers with complex social organization: food storage, wealth inequality, hereditary leadership, and elaborate ritual.

Singh and Glowacki call this the "diverse histories model." The Late Pleistocene wasn't a uniform sea of wandering egalitarians. It was a mosaic---with some groups living the classic nomadic lifestyle, and others already building proto-complex societies around coastal and riverine resource bases.

That's the empirical correction. Now for the speculative extension.

The Cyborg Hypothesis

Here's where it gets interesting. Intertidal shellfish can be gathered with bare hands or simple stones, but expanding into offshore niches---pelagic fish, marine mammals, distant islands---pressures the development of boats, nets, hooks, harpoons, fish traps. Direct archaeological traces of early watercraft rarely preserve, but we infer seafaring capability from island colonization. Humans reached Sahul by ~65,000 years ago, requiring open-water crossings. More strikingly, stone tools on Sulawesi date to at least 1 million years ago---meaning Homo erectus was crossing ocean barriers long before sapiens even existed. If our ancestors were seafaring a million years ago, who knows what they were capable of by 160,000 years ago.

This creates a feedback loop:

- Rich marine ecology → enables sedentism and social complexity

- Social complexity → enables specialization and technological innovation

- Better technology → unlocks new ecological niches

- Repeat

But this isn't just a chicken-and-egg story about tools. It's a claim about what we are.

The Aquatic Cyborg Hypothesis: Early Homo sapiens didn't just use maritime technology; we co-evolved with it. The boat wasn't a tool we invented after becoming cognitively modern. The boat---and the maritime adaptation it enabled---may have been part of what made us cognitively modern.

Think of the boat as an exosomatic organelle: an extension of the body that isn't genetically encoded, but is just as essential to the organism's phenotype as any organ. The relationship isn't organism → tool. It's organism + tool = functional unit.

The Steering Problem

This is where coherence dynamics enters the picture.

In my previous post, I argued that consciousness arises from a system's ability to steer through a high-dimensional state space. The "soup" (electrochemical dynamics) provides the terrain; the "sparks" (neural codes) provide the steering.

The Aquatic Cyborg hypothesis extends this logic to the evolutionary scale.

A terrestrial primate has a certain number of behavioral degrees of freedom: it can walk, climb, forage, fight, flee, socialize. Its "state space" is constrained by its anatomy and its environment.

Now give that primate a boat.

Suddenly, the accessible state space expands dramatically. New resources (pelagic fish, marine mammals, distant islands) become reachable. New social configurations (sedentary villages, stored surplus, division of labor) become viable. New cognitive demands (navigation, seasonal timing, complex tool maintenance) become selectable.

The technology doesn't just add options. It transforms the topology of the organism's behavioral manifold.

Consider the difference between terrestrial steering and marine steering. On land, you steer against friction---gravity, terrain, static obstacles. At sea, you steer against flow---currents, wind, waves. Steering against flow requires a higher-dimensional internal model. You must predict vectors, not just positions. You must anticipate how the environment will move, not just where it is. (If you aim a boat at a point, current and wind will drift you off course; you must model a moving field, not a static path.)

The boat didn't just expand where our ancestors could go. It forced a cognitive upgrade in how they modeled the world---from static obstacle-avoidance to dynamic flow-prediction. New dimensions of freedom, new dimensions of cognition.

The Low-D Controller / High-D Terrain Pattern

Notice the structure: a relatively low-dimensional intervention (building a boat) unlocks a high-dimensional expansion (new ecological and social possibilities).

This is the same pattern we see in:

- Neurons and fields: Low-D spike codes steer high-D electrochemical dynamics

- Genomes and development: Low-D genetic sequences steer high-D morphogenetic fields

- Rituals and societies: Low-D symbolic acts steer high-D social coordination

The boat is a low-D physical object. But it's a control interface to a high-D space of possibilities. The early human who lashed together the first raft didn't just build a transportation device. They built a dimensional amplifier.

What This Means for the "Human Revolution"

Archaeologists have long puzzled over the sudden appearance of "behaviorally modern" traits around 50,000 years ago: art, ornamentation, long-distance trade, complex burial practices. The standard explanation invokes a cognitive mutation---some neural rewiring that unlocked symbolic thought.

But maybe the revolution wasn't in the brain. Maybe it was in the extended system.

If maritime technology had been accumulating for 100,000+ years, gradually expanding the accessible state space, then the "revolution" might simply be the point where the system crossed a threshold---where the accumulated dimensional expansion became archaeologically visible as "complexity."

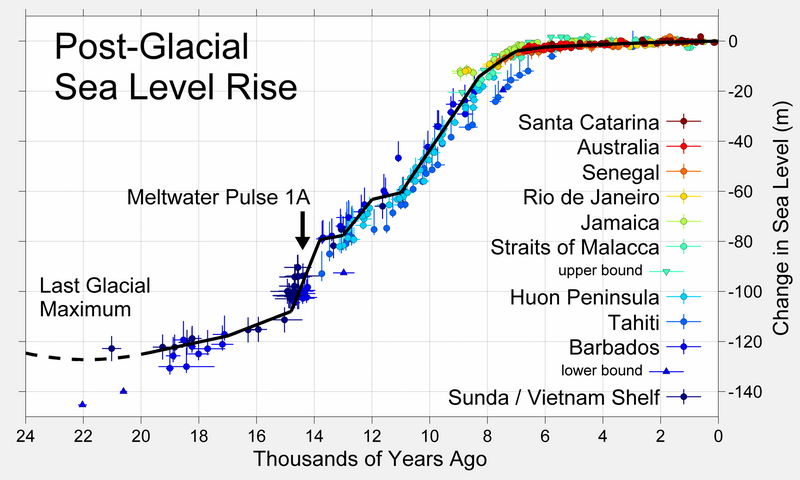

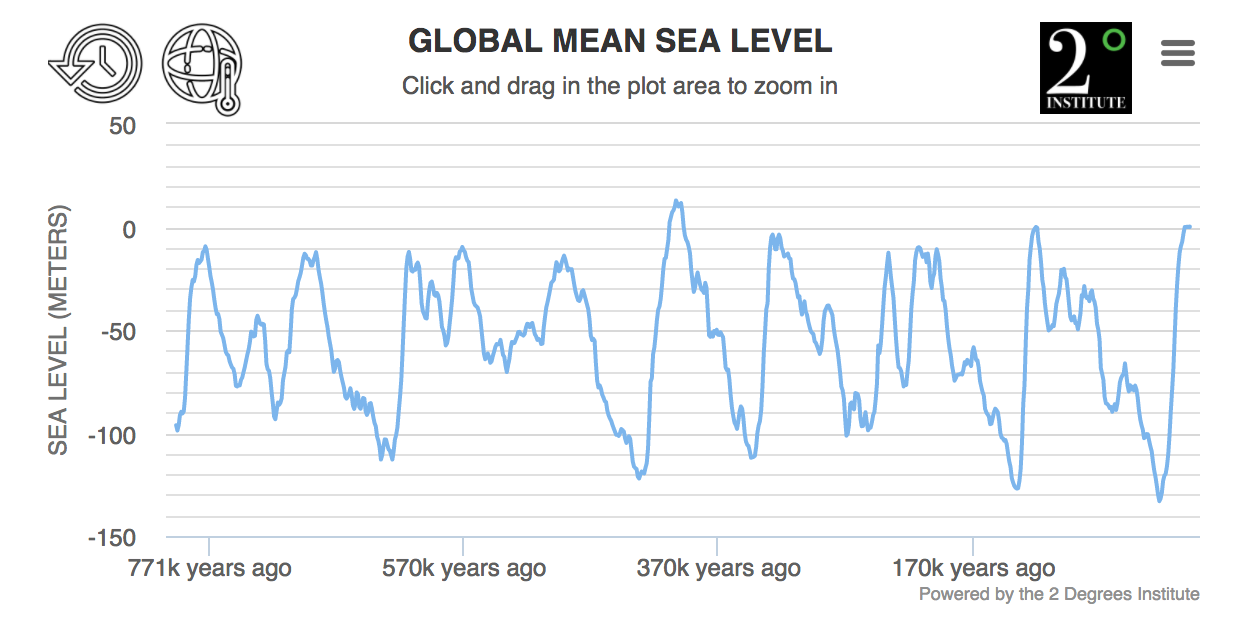

There's also a taphonomic bias to consider: during glacial periods, sea levels were 100-130 meters lower than today. Any coastal settlement from the Late Pleistocene would now be far out on the continental shelf, underwater.

The archaeological record should be sparse for exactly the environments where the Aquatic Cyborg hypothesis predicts the most action. Absence of evidence isn't evidence of absence---it's what we'd expect if the interesting stuff happened at the water's edge, and the water's edge has since moved kilometers inland.

There's another factor: megafauna. For most of the Pleistocene, inland environments were dominated by large, dangerous predators. Coastal peoples had little reason to venture into that terrain---the resources were poorer and the risks were higher. But between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago, megafauna went extinct across most continents. Suddenly, inland expansion became viable. Complex coastal societies---which may have existed for hundreds of thousands of years---finally moved into environments where their sites would be preserved and discovered.

The "Human Revolution" at 50 ka might not be humans getting smarter. It might be smart humans finally showing up where we can find them.

The brain didn't suddenly become capable of art. The coupled system---brain + boat + tribe---finally reached a configuration where art became selectable.

The Egalitarian Myth

This reframes the political implications of human evolution.

If the "natural" human state were egalitarian nomadism, then hierarchy is a deviation---an imposition, a fall from grace. A lot of popular discourse about "human nature" implicitly relies on this assumption.

But if Singh and Glowacki are right, there was never a single "natural" state. Our ancestors were diverse. Some were mobile and egalitarian. Some were sedentary and hierarchical. The difference wasn't cognitive or moral---it was ecological. And the pattern wasn't unique to coastlines: any "dense, rich, and predictable" resource base---salmon runs, nut groves, oases---could support similar trajectories.

Hierarchy isn't a corruption of human nature. Egalitarianism isn't our default. Both are solutions to different environmental and technological configurations.

This doesn't resolve political questions about how we should organize society. But it does suggest that appeals to "human nature" are less informative than we thought. We're not fallen egalitarians. We're not natural hierarchists. We're cyborgs---organisms whose nature is inseparable from our technological and ecological context.

What Would Prove Me Wrong?

If the Aquatic Cyborg hypothesis is correct, we should expect:

- Archaeological evidence of maritime technology predating "behavioral modernity." (The whale barnacles at Pinnacle Point are suggestive, but we need more.)

- Comparative patterns showing that maritime-adapted populations worldwide independently develop similar social complexity signatures, controlling for other variables.

- Cognitive traces of maritime adaptation in modern human psychology---perhaps specialized intuitions for navigation, seasonal timing, or fluid mechanics that aren't easily explained by savanna ecology.

If maritime technology was incidental to human evolution, we shouldn't see these patterns. If it was foundational, we should.

This post draws on Singh and Glowacki's "Human social organization during the Late Pleistocene" in Evolution and Human Behavior (2022). For a broader argument against the "nomadic-egalitarian" baseline, see Graeber and Wengrow's The Dawn of Everything (2021). The connection to dimensionality is developed in my papers on High-Dimensional Coherence and Substrate Dimensionality.